In this post I’m going to cover the inspiration, methodology and conclusions behind the interactive map of crime in Puerto Rico I’ve built. If you haven’t already done so, you can explore the map here. This has been a passion project of mine that I hope sparks a conversation and interest in the current state of security in the island as well as the role of data analysis in our understanding of large and complex social issues.

Why Build This Map? - Crime is regional

Earlier in 2019 it was impossible to tune into any Puerto Rican media outlet that was not discussing the current state of security in the island. The then governor Ricardo Rosselló and local congress where in a fierce debate on how to address a historic crime wave and aid a struggling police department that found itself stretched incredibly thin in its capacity to address the complex social aftermath of the disruptive 2017 Maria Hurricane. Upon the recent chat leaks sprawled from the telegram scandal, we see now how crime rates were a daily preoccupation for top government officials and a bar by which they measured their own political success. Even though this conversation is in no way new and was quickly overshadowed by concurrent facets of the ongoing fiscal crisis, it imprinted in me a feeling distress and uncertainty for the well being of friends and loved ones back home. As the political and social dismay were being expressed in the public sphere I found myself struggling to find any updated information or research about crime incidences in Puerto Rico after 2016. The police department has always done a great job of making general statistics of crimes publicly available but to be honest when you browse through these you really don’t see a drastic departure from the normal and unfortunate trend of rising crime waves across the island. I realized then, that most of what was driving this conversation was the push of a collective narrative from individual residents living in the island, who have a first hand account of the crumbling state of security in their homes and businesses.

In my search for more solid evidence I recalled the time when I was looking for my first apartment in Philadelphia. I stumbled upon a great resource map from the real estate website Trulia that allowed me, from the comfort of my home in Caguas, to browse a spotted map of crime in the west Philadelphia region. It colored each neighborhood based on how secure that region had been in the last year. That tool was instrumental in my search for a new apartment to live throughout grad school. I surely thought there must be an equivalent version of this for my island. But I was wrong, the closest thing I could find was a map published on the website of the police department that showed all the crimes occurred in the last six years all on top of each other.

The constellation of dots on the screen painted a really weird picture of crime in Puerto Rico. One in which you can barely find a place on the map free of dots since the information is so stacked and overlaid on top of each other. You can zoom in to familiar places you know and witness what criminal activity has occurred. But upon further inspection, you’ll find it rather laborious to tell whether something happened last week or 5 years ago. So here I was, standing in front of exactly the type of data I was looking for but could not extract any defensible conclusions from it. That’s when I realized a crucial fact that inspired me to make my own map and it is the realization that although crime is by its very nature an incidental phenomenon, security is on the other hand is regional.

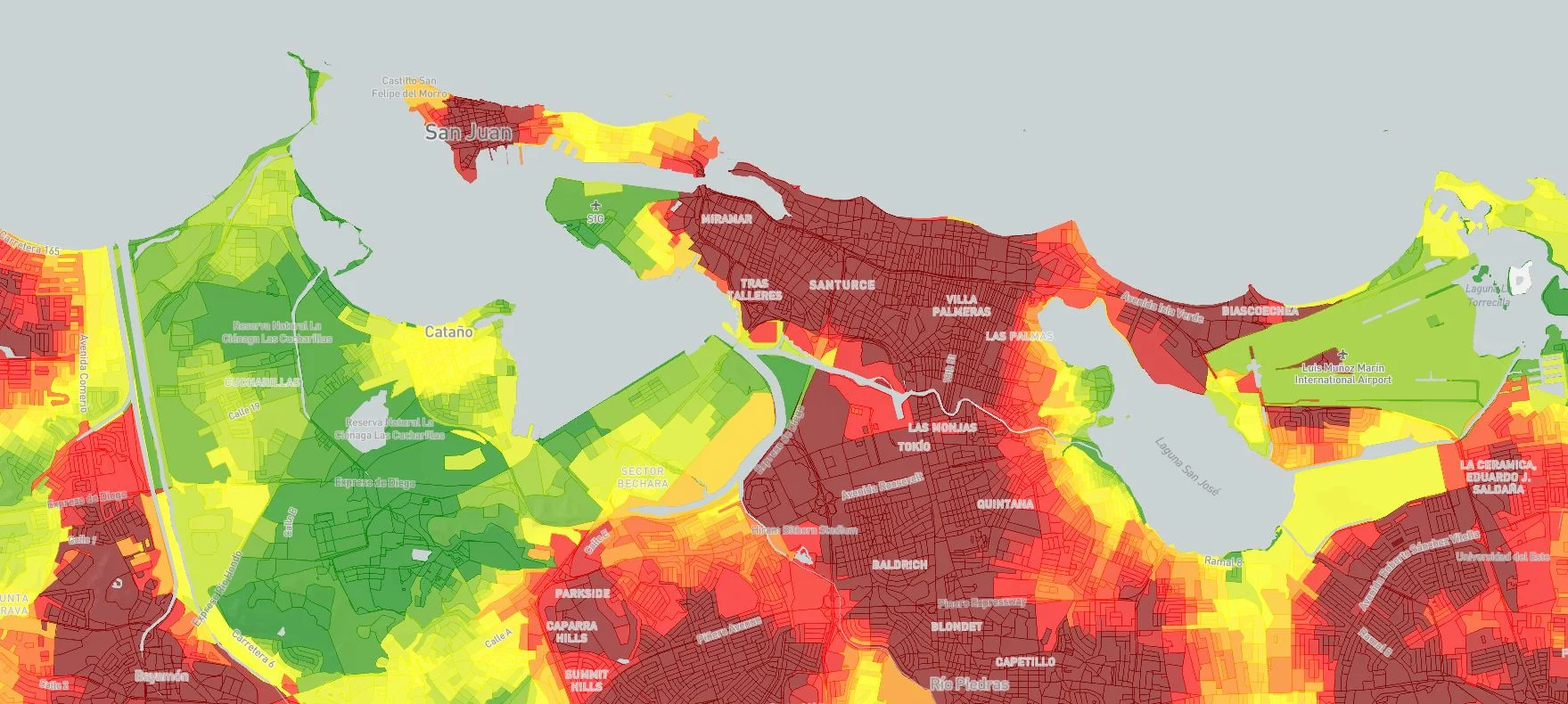

Security is an emergent property of an urban space or location. Meaning that it is not informed by any one thing, rather its the collective nature of a group of individual actions that add to the sense or therein lack of security. Security is more akin to rate. It needs to be talked about as a collective entity. Yet security must have its boundaries. The funny thing is that these boundaries do not come in the statistically-friendly hard shape of counties, they are in fact rather soft. What entails is that a single point in space cannot be said to be secure without taking into account all the other instances around it. Hence, I set out to portray a map of crime in Puerto Rico with this definition in mind. One that translates the point-like occurrences of criminal activity into a gradient understanding of security throughout the spatial domain of the island.

General Methodology

I took me about 4 months from conception to generate the final version but that included teaching myself a working knowledge of Arcgis, Javascript and Mapbox GL as well as overcoming certain hurdles with obtaining and analyzing the crime data.

The first step was to download the latest census block shapes from Data.gov. I made the decision of using the block shapes because inherent in them are notions of discrete communities and residential zones that I think are good descriptors of urban space and are familiar to many residents.

From there I started to compile the crime data sets made available through Puerto Rico’s open data portal. Much like the police department’s map, this tool from the government allows you to visualize and browse the data, providing the added option to export the data into an excel spreadsheet. I initially developed this map using data sets ranging from 2015 to 2016 yet, once I got it in a good place, I started to look around for the crimes for 2017 and onward yet was ultimately held back by the inability to download these from the portal. I searched throughout the months for the data, sending numerous emails to the police department but received no response whatsoever. The solution eventually came from a blog run by the Southern California Government GIS User Group that describes how to query and extract features from an ArcGIS hosted map service, using python. Seeing that the original crime map in the police’s website was built using the same hosting service, I proceeded to pivot my production using the ArcGIS Pro software for querying, analyzing and exporting my custom crime map.

Originally I had used the tools available at my disposal. As an architect I’ve developed a robust enough knowledge of Grasshopper for Rhino that I was able to script a prototype of the map complete with filtering and analysis of the crimes that occurred in each block. This was instrumental in my development of the project and motivated me along the way, but upon learning to work with ArcGIS I found its algorithms to be far superior in terms of speed and accuracy for analyzing large data sets.

Once I had the all the data filtered and organized by year in ArcGIS, I used the Spatial Join Tool to actually count the number of crimes occurred in each block. Extremely important in this process was making sure that I was not only taking into account the crimes that happen to lie inside of each shape but those that were positioned withing a 0.5 mile radius from the shape’s centroid as well. This is a trick I picked up from Glen Robertson’s blog, who was one of the original creators of the Trulia Crime map. Glen realized that “A radius count allows the data to be smoothed across adjacent blocks, as opposed to counting points in each polygon where the blocks stand out a lot more”. His project is incredibly smart in the sense that in continuously generates tiles based on newly reported crimes from crimereports.com. It is ultimately unfeasible to implement a similar solution in Puerto Rico due to the fact that crime statistics are not shared in such a dynamic and frequent way as they are in other communities across the mainland. It just seems to be the political and infrastructural reality of our island at the moment.

Yet, unlike the Trulia map I do not normalize the color range based on the minimum and maximum crime counts throughout the blocks. Instead I decided to approach this feature in a more robust and statistically sound manner. The max deep red color is associated with the second deviation from the mean of the total crime count in each block. This means that wherever deep red shows up in the map, it represents a block that is in the 2% range of regions that had the highest number of crimes committed in that year. All other blocks with crime counts beneath that are distributed linearly on the RGB scale all the way down to Green which represents 0 crimes. Once I had that range established for all the years, I took the personal decision to average all the max clips to get a global distribution applied uniformly throughout all the years. This basically ensures consistency across the years so that as you toggle through different years the meaning of the colors remains the same. The average of the max clip of from the years of 2012-2018 came out to be 234. This is not a magical number in it of itself, but it is a way to distance my judgement (with inherent bias it may carry) from the statistical analysis in the map.

In order to provide viewers confidence in the crime count, I included the precise location of each incident taken into account on the map. The incident reported in this data set all fall under the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIRBS). Specifically those that belong to Group A and Group B which classify offences that either fall under a law enforcement agency’s jurisdiction or those that led to any arrest. The police department of Puerto Rico further groups these incidents within their data sets into the following: Type A categories: 1 Homicide, 2 Rape, 3 Robbery, 4 Assault, 5 Trespass, 6 Burglary, 7 Motor Vehicle Theft, 8 Arson and 9 Other. Because the latter is a more simple and broader description of the occurrences it is the classification system I chose to display. When toggling the crime incidences you’ll see every instance represented by a colored dot representing which general category it falls under.

CONCLUSION & Limitations

As with any view on crime this approach does not come without its inherent limits. Throughout the design process certain assumptions were taken that affect the way one might read the map. I’ve gathered here a small list of the limitations I can pinpoint within this methodology, which are all points on which the project can be further improved upon.

Limit: This is not a weighted view of crime

First of all, I’d like to point out that what is displayed here is a general mapping of overall crime. Meaning, that there is no weight between different types of crimes. We don’t incorporate any accountability for the ways that a murder might be more impactful to a community than a mere trespassing. Doing so would require us to assign arbitrary values and weight to the nature of different crimes. One way One might correct this is by measuring the economic impact of the offence, of which plenty of research has already been done, and weighting each crime in accordance to that scale. Yet, for the purposes of this project I opted for the simplicity of fact that what we are presenting here is a representation of general criminal activity.

Limit: This exercise does not control for population.

If you’re familiar with the island, one of the first things you’ll notice is that criminal activity tends to congregate in and around heavily populated urban areas. This is a phenomenon that will be present in most urban studies and one which can be statistically corrected by controlling for population. In my personal search for population data for each block I was surprised to find the data sets that were rather spotty and unreliable. Certain blocks which I personally knew where populated where classified as being vacant. This caused me to doubt the accuracy of the data set. Furthermore, its been heavily reported that Puerto Ricans have engaged in mass emigration to the mainland due to economic and environmental factors such as the 2017 Maria Hurricane within the last five years. This leads me to believe that any population data prior to 2017 might grossly misrepresent of the current state of the island and we might as well wait for the upcoming 2020 census to get reliable numbers. Due to these factors I took the personal choice of not publishing the version of the map controlled for population on the grounds that I cannot be confident of its accuracy.

Limit: We must recognize the inherent bias in the data sets we are operating with

It would be unwise to overlook the fact that there is inherent bias in the confection of this crime database. Any gathering of incidents holds the mark and ideals of the Police of Puerto Rico and the methods or limits by which they operate. This pertains to their targeted regions as well as any limits within their cataloging systems and personnel available to cover the physical realm of each community.

On this last point I’ll reserve any personal opinions I might have on this matter but will be unyielding in uncovering the defensible conclusions you can gather from the study. The following list covers the most important conclusions I’ve gathered throughout the process.

Conclusion: There were clearly unpoliced and underrepresented regions after the Maria Hurricane.

We can see drastic changes happening after September 2017. Particularly in more rural and isolated areas where all of a sudden the normal crime rates drop or increase drastically. This is representative of a whole slew of unknown variables that expose the limits of crime statistics and police accountability more than any other factor. One crucial example of this is seen in Bayamón. In this heavily populated urban region one can see crime rates increasing steadily from 2012 to 2016. Yet when you browse through 2017, the rate of incidents drastically drops and the eastern side of the city turns a “safer” shade of yellow-green. It is rather unlikely that Bayamón all of a sudden got that much safer. No, what we’re actually seeing here is a nefarious fact surfacing out irregularities with the reporting. It’s suggestive that this region was grossly underrepresented in terms of police presence during 2017. A case in which the police shines by their absence. Such cases can be found all around the island as well. Places where 2017 seems safer than other years actually reveal a fluke, one that is indexical to lack of security and unstable conditions under which residents lived throughout the grueling months after the hurricane.

Conclusion: Puerto Rico did get more dangerous, but not everywhere.

Seeing Crime in this way reaffirms old conceptions of security in the island and debunks many others. Such as the idea that Puerto Rico is an inherently dangerous place. Like many other places there are hotspots of criminal activity, specially around urban areas. Yet, when you see the island as a whole, you cant miss that most of it is considered by these standards quite safe. Some of the insightful conclusions the map provides stem out of the ability to browse through different years, where you’re able to trace the organic evolution of crime in different regions. Below is a list of what I found in certain areas of interest when browsing through the years.

The Metro Area got less holistically dangerous.

Caguas got less holistically dangerous.

Old San Juan’s crime increased very slightly

Carolina and Cupey got a whole lot more dangerous

Non-metro populated towns increased their crime counts steadily throughout the years. But geographically remained pretty much the same.

I’d like conclude by saying that this project has been incredibly rewarding and insightful to work on. At the same time I believe it’s in a point where it should be vetted and take upon further by others interested in this space. If you have any interest in taking this further I want to hear from you. I hope this sparks a conversation about the state of security in our island and I hope that it provokes more novel approaches to the visualization of big data in Puerto Rico. Certainly people have a need for transparent and accurate depictions of public services. If you’re interested in talking with me shoot me an email using the contact page in this site.

Your’s truly,

Ramon